Table of Contents

ToggleQuick Answer: The Cost of Recording an Album for Indie Artists

Recording an album as an independent artist typically costs between £2,400 and £5,000. That’s exactly what Spencer Segelov, a Cardiff-based indie musician, has spent across nine albums. His story shows how those costs add up- and why recording is often worth it, even when promotion isn’t.

How Much is the Cost of Making An Album as an Indie Artist?

You can spend £3,000 on an album and still feel invisible.

That is the reality Spencer Segelov has lived through as an independent artist for more than 20 years. The costs pile up: studio hire, mixing, mastering, artwork, and promotion. Too often, the return is silence.

For Spencer, the question “how much does it cost to record an album?” has never been just about money. It is about the financial, cultural, and personal price of surviving as an indie artist in today’s music industry.

Meet Spencer Segelov

Based in Cardiff, Spencer Segelov has been making music since the late 90s. Over more than 20 years he has played in bands, released nine solo albums across multiple genres, and poured thousands into recording, artwork, and promotion.

His career is a window into what it really costs to be an independent musician. In this interview, Spencer shares the real numbers, the changes he has witnessed in the industry, and the lessons he has learned from two decades of creating music.

Q: What’s your stage name, and how did you choose it?

Spencer:

“It’s my real name [Spencer Segelov] and I am the only person on planet earth with my name so it’s easy.”

Spencer’s story, though, isn’t just about his name or where he comes from. It is tied closely to the shifts he has witnessed in the music world around him. Based in Cardiff, he has lived through the rise and fall of very different local scenes.

The Local Scene: Then and Now

“Today many musicians survive by playing covers or weddings. It feels like a return to the troubadour days.” – Spencer Segelov

Q: Where are you based, and how has your local scene shaped your music?

Spencer:

“I’m based around the Cardiff area. I’ve been playing in bands since 1996 as a drummer, and I’ve been making my own music for about 20 years as a solo artist.

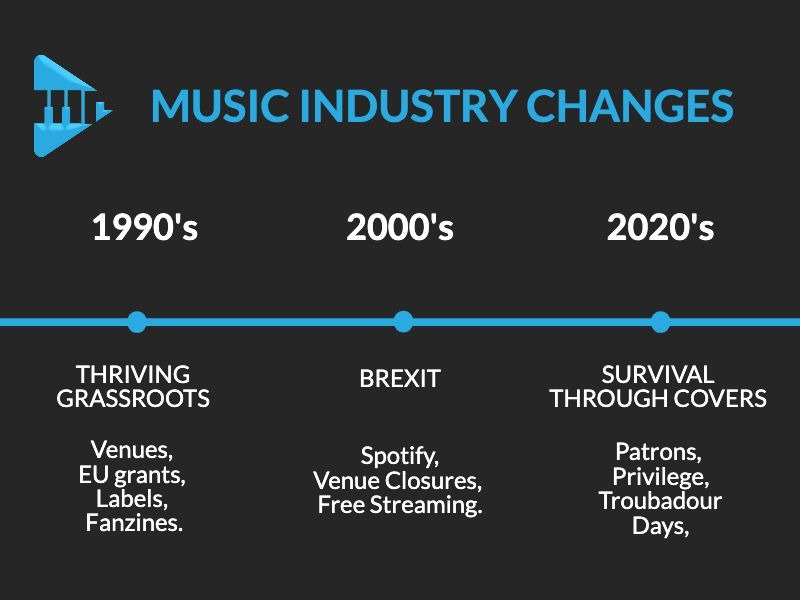

In the late 90s and through the 2000s there was a strong scene. You had promoters, bands, indie club nights, grassroots venues, fanzines, radio shows and small labels. A lot of money came from Europe to support projects and festivals. There were grants that helped working-class people record EPs, play gigs in Europe, even make music videos.

At that time, you could play a gig every week, have it reviewed in several magazines, and meet other bands from across the UK. There was a real sense of cross-pollination – ideas moving around, musicians supporting one another, and a system that kept things moving.

By the 2010s that ecosystem had disappeared. Brexit made touring in Europe harder, funding dried up, venues closed, and streaming meant recorded music became free for the first time. The indie label system collapsed, small tours became a financial loss, and original music turned into something mainly for the privileged.

Today many musicians have to supplement original music with covers or weddings to survive. Some rely on patrons or family support. It feels like a return to the troubadour days, where musicians were either scraping by or supported by sponsors.”

Listening to Spencer, you hear not just nostalgia but the weight of an industry that changed underneath artists’ feet. His story reflects the wider development of the music industry – from a thriving grassroots ecosystem in the 90s and 2000s to the survival mode many independent musicians face today.

The Real Cost of Making an Album

Beyond the shifts in the music scene, the financial side of being an artist brings its own pressures. Recording, mixing, mastering, artwork and promotion all add up. For Spencer, recording has always been the biggest expense, and sometimes the most rewarding.

Q: Walk me through the main things you’ve spent money on in your career – recording, artwork, distribution, promotion. How much do you think you’ve invested overall?

Spencer:

“Recording an album is still the biggest cost, and I don’t mind paying for that. I want the music to sound right and at a good quality. Over the years I’ve learned to record some of my own parts, but I can’t mix or master, which I think is common among musicians.

The money usually goes on rehearsal room fees, studio hire, producer fees, mixing, mastering, photography, artwork, pressing CDs or vinyl, paying radio pluggers and hiring publicists for magazines. You can easily spend £5,000 without a single person even knowing your music exists.

Even when I recorded a short nine-track solo album and used mates’ rates for everything, it still cost around £2,400-£3,000 before making any physical copies like CDs.”

Breakdown of a Typical Album Session

- One day recording piano and acoustic guitar with a producer

- Two days to record vocals, including backing harmonies and minimal guitar overdubs

- One day to track drums, percussion and bass simultaneously in a live room with a producer

- Five days of mixing (two songs per day to save costs)

- Mastering

Photography and design

Spencer:

“I used to run a small label with friends. We tried to distribute my recordings to indie record shops and help with promotion, but it was always an uphill battle.

I’ve made nine albums across nine genres, and they vary a lot in cost and time. One was recorded in a single day with gig money – just voice and piano moods. Another was recorded and mixed in three days, a folk/country album that tried to capture the sound of early recording technology. The most expensive project was a 13-piece chamber orchestra double album, which took a few weeks to complete.

Wherever possible I try to do everything in one day (all the guitars in a day, all the vocals in another) and I play most instruments myself to keep costs down. Even so, I’ve found that the albums I made cheaply haven’t attracted much attention.”

What stands out in Spencer’s story is that recording itself feels like money well spent. It is the part of the process he can point to with pride, something lasting that justifies the cost. Promotion, on the other hand, has been unpredictable. Too often it costs more than it gives back.

Independent artists often face the same dilemma. Do you keep pouring money into PR campaigns, or do you build practical tools that last? An electronic press kit is one way to make sure the investment works for you long after a single campaign ends.

Album Cost Snapshot

| Category | Spencer’s Experience | Typical Range (UK) |

| Studio + rehearsal | 4-5 days across instruments | £800-£1,500 |

| Mixing | 5 days at 2 songs/day | £1,000-£1,500 |

| Mastering | Outsourced per track | £300-£500 |

| Artwork & photography | Friends helped, but still invested | £200-£500 |

| Promotion (PR/pluggers) | “A random coin toss” | £500-£2,000 |

| Physical product | Optional CDs or vinyl | £500-£1,500 |

Even a stripped-back project can cost around £2,400, while a more ambitious release can easily pass £5,000. The financial cost of being an artist is not only about making the record. It is also about taking a chance on promotion, knowing it may not bring anything back.

Q: Looking back, which of those felt worth it, and which felt like money that just disappeared?

Spencer:

“Recording costs have been worth it and it’s something you can listen back to and feel proud of. Promotional costs have always been a random coin toss. I’ve definitely spent hundreds of pounds and had no return, with no comeback to the company who have taken the money.

The one thing you can’t seem to do cheaply is have a good-sounding record. Without a good-sounding record, you’d have nothing to promote.”

“Recording costs have been worth it. Promotion has always been a random coin toss.” – Spencer Segelov

His words underline the lesson every independent artist eventually learns: recording is the foundation. If the record itself isn’t strong, no amount of marketing can carry it. Promotion has its place, but it is unpredictable.

Royalties and Income Streams

Q: When you hear the word royalties, do you think of it as something for big-name artists, or something every artist can claim?

Spencer:

“I receive money from PRS, and I’ve had a few friends with songs placed in TV programmes or adverts. One friend has even managed to make a living from the royalties of just a single song.

I’ve also received money at times when my songs have been played on the radio, or when I’ve performed live on the radio myself.

When it comes to adverts and other media, royalties usually come through a publishing deal. I don’t have a publisher, so I don’t really have a way for people to hear my music or for it to be promoted and pushed into those spaces.

More recently, there have been examples of bands earning royalties through TikTok without a publishing deal or label, so there are other ways in now.

I also know friends who have earned significant amounts from PPL, but I’ve always struggled to understand how PPL works.”

(If you struggle to understand too, you can learn more about PPL here.)

Spencer’s experience shows how royalties can feel both promising and confusing. He has received money from PRS, seen friends thrive through syncs and PPL, and knows that sometimes one song can make a huge difference. At the same time, the lack of clarity around publishing and performance rights means many artists miss out.

For independent musicians, this is a common reality. Without the right registrations and knowledge of how societies like PRS and PPL work, income can easily slip through the cracks. That is why tools like Melody Rights exist – to simplify the process and make sure artists don’t lose money that should already be theirs.

Without the right registrations, income can vanish. For a full breakdown of how each stream works, see our guide on 4 types of music royalties explained

PRS for Music collects royalties for songwriters and publishers, while PPL collects for recording rightsholders. Both are essential for UK artists (PRS official site).

Lessons Learned After 20 Years

Q: If you had one piece of advice for a new indie artist, something you only learned through pain and struggle, what would it be?

Spencer:

“Never change genre with each album if you want to build a fanbase. People say they are into all sorts of music, which may be true, but they do not like to see the same artist switch between genres abruptly. They can handle a gradual change, but not a sudden one.

Also, never record an album with a 13-piece chamber orchestra, even if it is your dream. It’s very expensive.”

“Never change genre with each album if you want to build a fanbase.” – Spencer Segelov

There’s a dry humour in Spencer’s words, but also hard-earned wisdom. The first lesson is about consistency. Listeners want to grow with an artist, and sudden shifts in style can break that connection. The second lesson is about realism. Dreams are powerful, but they need to be matched with resources, otherwise they can drain an artist before the music has a chance to reach anyone.

Career Highlights

Q: We love to celebrate artists who share their story. What’s a recent highlight of your music career, or something you’d like to celebrate today?

Spencer:

“My last album, my ninth, briefly charted in Scotland in 2024, which was unexpected, even if it was only at the low end of the charts and only for a week. Recently I also played a gig celebrating 20 years of my music with a 10-piece band in a church, and we had more than 100 people come.”

These highlights don’t erase the struggles, but they show the persistence it takes to keep going as an independent artist. For Spencer, the cost has been measured not just in money but in years of dedication, and those moments of recognition carry weight because of what it took to get there.

The Real Price of Being an Indie Artist

Spencer’s story shows that the true cost of being a musician is never just financial. It is cultural, personal and administrative. Recording costs money. Scenes rise and fall. Persistence takes its toll. Royalties often go unclaimed.

Even with all of that, the wins matter. A charting album. A packed church for a 20-year gig. The pride of recordings that last. These moments remind artists why they keep going.

For independent musicians, the challenge is making sure the investment of time and money does not disappear into the cracks of missed registrations or lost royalties. That is why we built Melody Rights – to give artists like Spencer the tools to protect their catalog and make sure the income they earn finds its way back to them.

Don’t let your music work for free. Register it, protect it and make sure it pays you back.

FAQs: Album Costs and Indie Artist Income

How much does it cost to make an album?

For independent artists, costs typically range from £2,400 to £5,000 or more. Spencer Segelov’s experience reflects this: studio time, mixing, mastering, artwork and promotion all add up quickly.

What is the biggest cost when recording an album?

Recording itself (studio hire, mixing and mastering) is the most consistent expense. Promotion can often cost just as much, but is far less predictable in terms of return.

Can independent artists make money from royalties?

Yes. Royalties are not just for big-name artists. With the right registrations (PRS, PPL, The MLC, and Content ID), independent musicians can collect income from streams, radio play, live performance and sync opportunities.

How can indie artists avoid wasting money on promotion?

The key is to invest in tools that last, like an electronic press kit, rather than one-off promo campaigns. PR can help, but without a strong foundation, it is often a gamble.