When people ask what is a music catalogue, they’re usually thinking about folders. Most artists don’t start with a system. They start with clarity, because everything still makes sense.

At the beginning you recognise every file, you remember which bounce you sent and why, and nothing feels fragile yet because the work is still recent enough to live in your head rather than in a system.

Over time that certainty fades without anything actually breaking. You release more music, make small changes after tracks are “finished”, send files out in different contexts, and one day someone asks for a version you haven’t touched in a while and you realise you need to stop and think before answering.

The problem isn’t that your music is disorganised.

It’s that it was never treated as a catalogue in the first place.

Table of Contents

ToggleWhat Is a Music Catalogue?

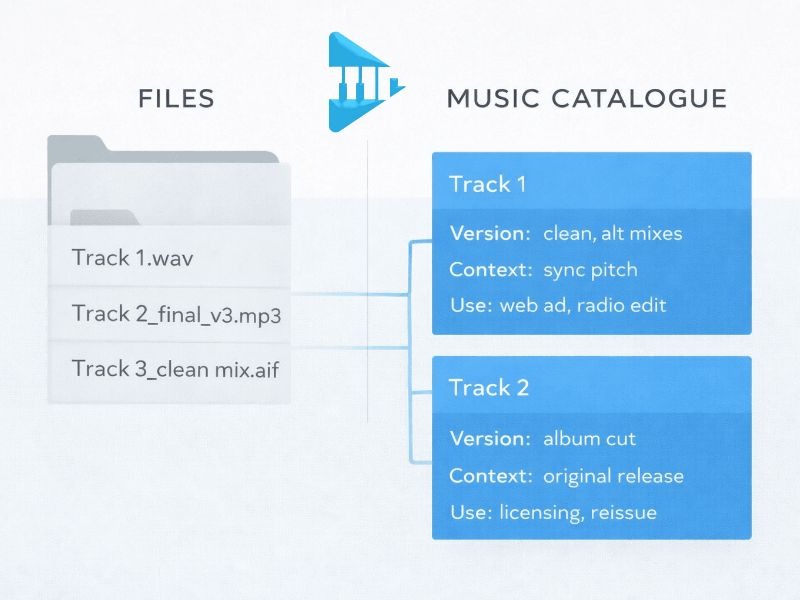

A music catalogue is a structured collection of musical works that preserves context, identity, and usability over time. Unlike a folder of audio files, a catalogue exists so music can be shared, returned to, and trusted across different situations, people, and stages of an artist’s career. It answers what the music is and how it can be used, not just where it’s stored.

In short, a music catalogue is how music stays usable once memory is no longer reliable.

You’ll see the terms music catalog and music catalogue used interchangeably. They mean the same thing: a structured way of organising music so it can be understood, reused, and relied on over time. This isn’t about storage. It’s about long-term use.

Files Solve Storage. Catalogues Solve Use.

A file answers a very simple question: where is this stored?

A catalogue answers a more demanding one: what is this, and what can it be used for now and later?

A catalogue assumes movement, reuse, and context. The same piece of music might resurface months or years later, in a different situation, for a different reason, with different expectations attached to it.

When music is treated as files, its usefulness depends on memory. When it’s treated as a catalogue, usefulness is built into the structure itself.

A music catalogue is not a cloud drive, a backup, or a folder system, even though it may contain those things. Its role is not to hold music, but to make music usable as time passes.

Why the Music Industry Treats Music as a Catalogue

The music industry didn’t adopt catalogues for aesthetic reasons. It did it because music doesn’t live one linear life.

A single piece of music might be released as a standalone track, folded into an EP, revisited years later for a compilation, or reused in a completely different context altogether. The music itself doesn’t change, but its role, presentation, and expectations do.

A catalogue exists so everything still makes sense once music stops moving in a straight line. That’s what allows tracks to resurface in contexts you didn’t originally plan for.

That’s why labels don’t manage isolated songs. They manage catalogues. Bodies of work are revisited, reissued, licensed, and recontextualised over time, sometimes decades after release. Publishers think the same way, not in individual files, but in collections of works that continue to generate income and relevance long after their first release.

Libraries exist for the same reason. In licensing, publishing, and archival contexts, music is expected to travel across projects, platforms, people, and years. A catalogue is what makes that movement possible without confusion.

It isn’t about control.

It’s about continuity.

How Folder-Based Organisation Quietly Breaks at Scale

Most catalogue problems don’t come from neglect, they come from momentum.

Each release adds a little complexity. A new version, a late tweak, an updated artwork, a link that never quite gets replaced. Nothing breaks loudly, but over time it becomes harder to trust what you have.

The issue isn’t the folder. It’s that the music has started to move beyond its original moment, in ways the original structure was never built to support.

As Bobby Cole, Managing Director of Melody Rights, puts it:

“Most artists don’t realise they have a catalogue problem until something small breaks. A file request, a missing version, an old link that’s still being used. By the time they notice, the issue isn’t storage, it’s trust.”

That frustration shows up outside the industry too. As one music collector put it when venting about their own growing library:

“It’s actually a pain trying to organize my music because nothing is standardized… now which album art do you use? Different metadata, remixes, live recordings – enough said?”

– Reddit user, r/musichoarder

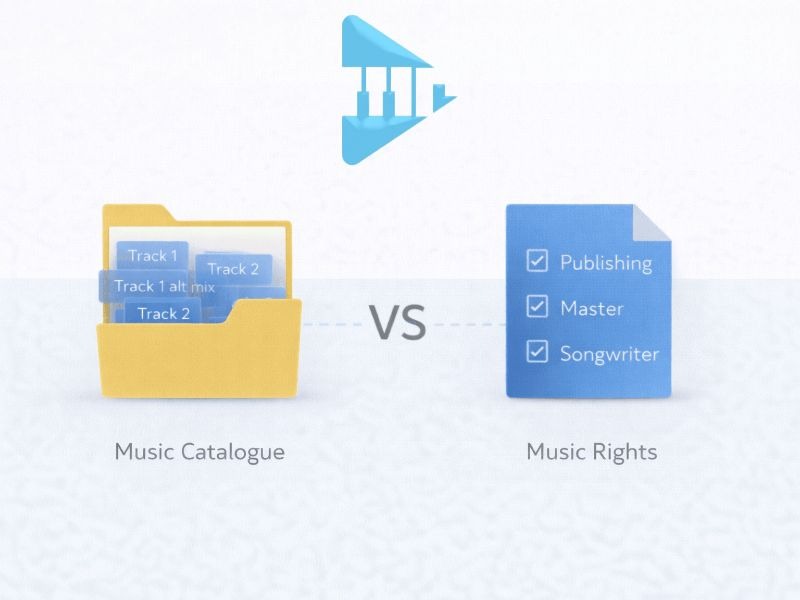

Is a Music Catalogue the Same as Owning the Rights?

Rights are part of a music catalogue, but they are not the same thing – see the difference between owning music rights and managing a catalogue for more detail.

A catalogue may include works you own, works you control, or works you administer, but the catalogue itself is the structure that holds those works together with their context. Ownership determines who gets paid. The catalogue determines whether the music can be understood, trusted, and reused over time.

Confusing the two is common, but they solve different problems.

Why Organisation Is a Creative Problem, Not an Admin One

Organisation is often framed as bureaucracy, something that sits between you and the creative work.

In practice, when a music catalogue is clear and trusted, creative momentum improves. Less energy is spent second-guessing, and more is spent making confident decisions.

A catalogue isn’t about tidiness. It removes friction so your music can keep moving, even when your attention is elsewhere.

The longer music is expected to live, travel, and be reused, the more essential this kind of structure becomes.

This shift in thinking comes before tools, systems, or workflows. Until the problem is understood properly, any attempt to “fix” it tends to fall back into the same patterns.

This kind of structure also makes it far easier to protect your work and keep the details around it consistent. Learn how to protect your music and keep your details straight.

A Note on Structure

This way of thinking shows up in tools that treat music as a structured catalogue rather than a loose collection of files. The point isn’t the software itself, it’s the shift in mindset, from storing music to supporting its long-term use.

Platforms like Melody Rights are built around this idea, but the principle applies regardless of what system you use.

The Quiet Truth About Music Catalogues

Music rarely stops working because it isn’t good enough.

More often, it stops moving because it becomes hard to use, hard to trust, or hard to understand once time has passed. Catalogues exist to preserve meaning and context so music remains usable long after the moment it was created.

That’s why a music catalogue isn’t just a place your music lives.

It’s the structure that allows it to keep living.

Understanding catalogue structure is part of the same foundational thinking behind long-term success, the kind explored in how to start a music career with foundations that last.

Fact-checked by Bobby Cole, music rights specialist.