Table of Contents

ToggleQuick Answer: How Music Gets Chosen

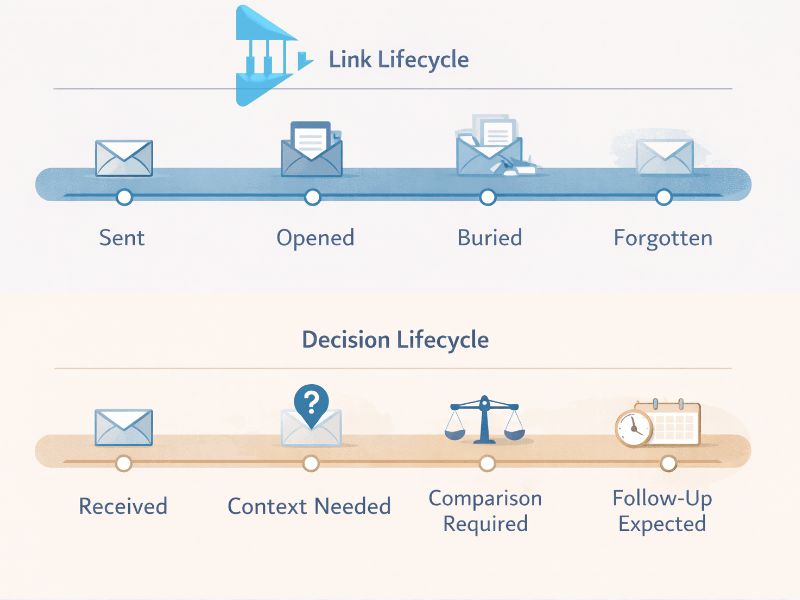

Music usually isn’t chosen in one clean listen.

It’s compared against other tracks, dipped into briefly, then revisited later, if it sticks at all.

People making decisions rely on context and memory, and on being able to come back without friction. Streaming platforms are built for continuous listening, not for holding attention across days or decisions. That’s why sending music links so often leads to silence.

How Music Gets Chosen: Streaming link vs decision playlist link

| What the listener needs | Streaming link (Spotify/Apple Music) | Decision playlist link (private shortlist) |

| Purpose | Listening and discovery | Reviewing and choosing |

| Multiple tracks | Possible, but not built for comparing options | Built for shortlists and comparison |

| Returning later | Easy to forget in the flow | Designed to be revisited |

| Sharing internally | Not designed for team handoffs | Easy to forward and discuss |

| Context and notes | Minimal | Built around context and selection |

| Control | No expiry | Can be set to expire |

If the goal is a decision, the format has to support comparison and return, not just playback.

What to send when you want a decision

- Shortlist 3–6 tracks, not your whole catalogue

- Label versions clearly (instrumental, clean, radio edit)

- Add one line of context per track (mood/use case)

- Include ownership clarity (master + publishing, one-stop if true)

- Make the next step obvious (“Reply with your top 2”)

(Optional) Use a link that can be revisited easily, and set expiry only if it helps the brief.

When reviewing music professionally, the process usually looks more like this:

- Compared against multiple tracks, not judged in isolation

- Listened to in short sections, not full playthroughs

- Revisited days or weeks later, not decided instantly

- Shared internally with notes, not emotional reactions

- Chosen based on usefulness for the project, not just personal taste

Playlists & Presentation

Two kinds of playlists

Artists usually hear the word playlist and think streaming. Spotify, Apple Music, that world.

But when people are choosing music professionally, a playlist often means something else. It means a private listening set, a shortlist of tracks shared as one link, built for comparison and returning later.

That second kind of playlist isn’t about streaming placement.

It’s a delivery format, a way to send a small, curated set of tracks to someone who needs to choose, not just listen.

It replaces MP3 attachments and messy drive permissions with one link that can be revisited, forwarded internally, and acted on later.

Why links feel neutral, then fail

Most artists don’t think too hard about how their music is sent out into the world. Sending music links feels neutral and invisible.

You paste it into an email, a DM, a form, and assume the music will speak for itself once someone presses play.

And at first, that seems reasonable. Streaming platforms are where music lives now. They’re familiar, frictionless, and always within reach. Dropping a link feels like the obvious thing to do.

The confusion only sets in later, after the replies stop coming. Not a clear rejection, not feedback, just silence. That’s usually when artists start questioning the music itself, even though nothing about the music has changed.

What’s rarely questioned is the way the music arrived.

How Is Music Actually Chosen?

How music gets chosen is rarely about uninterrupted listening.

In practice, people deciding what to do with a track listen in short bursts, compare options, revisit files later, and often share them internally.

Streaming platforms are built for passive consumption, not focused evaluation, which is why music sent as simple links often stalls without a clear decision.

This applies whether the decision is happening in A&R, sync, client work, or internal reviews where music is compared side by side.

Sync decisions make this especially visible… You can see that decision workflow in our breakdown of how sync licensing decisions actually work.

That gap between listening and deciding is where most of the confusion begins.

Streaming is designed to keep music moving forward, one track into the next, with as little interruption as possible. Decisions work in the opposite direction. They require pause, comparison, and a reason to come back. When those two environments are mixed up, the result is rarely a clear yes or no.

Streaming Platforms Are Built for Consumption, Not Decisions

Streaming platforms are incredibly good at what they were designed for. They make discovery easy, listening effortless, and sharing instant. They are places people go to enjoy music, not to assess it.

When someone is making a decision, whether that’s for a project, a playlist, a brief, or a recommendation, they’re listening differently. They’re not settling in for an album experience. They’re scanning, skipping, revisiting, and comparing. They might only hear thirty seconds now and come back later, if they remember to.

That kind of listening doesn’t sit comfortably inside a platform built around endless flow. Nothing is wrong with the platform itself. The problem is expecting it to support a decision-making process it was never designed to handle.

What People Actually Need When They’re Deciding About Music

When people are deciding what to do with music, they’re usually juggling more than one option and more than one responsibility. Attention is limited. Time is fragmented. Listening happens between other tasks, not in isolation.

What they need in those moments is clarity. A sense of what they’re hearing, why it’s relevant, and whether it’s worth returning to. They also need consistency, the ability to compare like with like, and confidence that what they’re hearing now will still make sense when they come back later.

That consistency often breaks down because music isn’t properly organised, which is why this guide on how to register your music properly matters more than most artists realise.

This isn’t about impressing anyone or dressing music up. It’s about making listening feel purposeful instead of accidental.

Why “Just Send Me a Link” Is Misleading

Most artists never hear a clear “no.” What they experience instead is silence. A link goes out, nothing comes back, and it’s easy to assume the problem is taste, timing, or quality. So the next time, another link is sent, usually with a little less confidence than before.

Music submission links work well for quick listening, but they are not designed to support professional review or decision-making.

What that phrase usually means, though, is convenience, not readiness. It’s a way of saying, “I’ll take a look when I can,” not “I’m about to sit down and make a decision.” In practice, the link joins dozens of others, arriving in an environment that isn’t built for focus or follow-through.

Links are easy to send and easy to open, but they’re also easy to forget. Once the moment passes, there’s often no clear reason to return, especially if the music isn’t immediately tied to a context or a next step. Nothing is rejected outright, it just loses momentum.

This is why silence feels so confusing. From the outside, it looks like a lack of interest. From the inside, it’s often just friction. The music didn’t fail. The way it arrived made it hard to act on.

How Music Is Reviewed Behind the Scenes

Behind the scenes, music is rarely listened to start-to-finish in one sitting. It’s dipped into, compared against other tracks, paused, revisited days later, or shared internally with a note like “worth another listen” or “maybe for later.”

Decisions are made gradually, not in one dramatic moment. They rely on memory, context, and ease of return. If any of those are missing, the music doesn’t get rejected, it simply slips out of view.

This pattern shows up repeatedly in sync, A&R, and client-based music decisions, where tracks are revisited and compared long after the first listen has passed.

“Most artists don’t have a music problem, they have a delivery problem. When the only thing you send is a streaming link, it’s easy to listen once and never return. A decision needs a shortlist that can be revisited, compared, and forwarded, otherwise the music doesn’t get rejected, it just loses momentum.”

– Bobby Cole, Managing Director, Melody Rights

That’s the reality most artists never see. Not because it’s hidden, but because it feels mundane from the inside.

Presentation Is About Removing Friction, Not Impressing People

Presentation often gets mistaken for branding or polish. In reality, it’s about making listening easy to continue. Music gets chosen when it’s simple to understand, simple to return to, and simple to place in context.

That clarity often depends on ownership and rights being obvious upfront, which is why understanding the difference between master rights and publishing rights directly affects how music moves through decisions.

The goal isn’t to stand out visually or feel clever. It’s to remove the small points of friction that stop music from getting a second listen. When those frictions disappear, decisions become possible.

This way of thinking is reflected in platforms like Melody Rights, where music presentation is treated as part of the wider workflow rather than an afterthought. The point isn’t the tool itself, it’s the shift in mindset, from sharing links to supporting decisions.

Presentation means giving music a stable home, clear context, and a reason to be revisited, not just a temporary listening moment.

The Quiet Reality On How Music Gets Chosen

Most artists never hear a clear “no.” What they hear is nothing. Silence fills the gap where feedback or direction should be, and over time that silence starts to feel personal.

In many cases, though, it isn’t about rejection at all. It’s about how music moves, or doesn’t, once it leaves your hands. When presentation removes friction, music has a chance to be reviewed on its own terms. When it doesn’t, even strong work can quietly stall.

Music isn’t chosen in the same environments where it’s streamed. Understanding that difference doesn’t change the music, but it changes how much opportunity the music has to keep moving.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

Fact-checked by Bobby Cole, music rights specialist.

______________________________________________________________________________________________